The small wood stove has heated the yurt quickly. Finally, having reached the camp in the valley of Ak Suu, we can relax, take off our jackets and warm our hands on a hot cup of chai. Our butts are sore from riding on horse back for four hours straight but in Kyrgyzstan it’s a normal means of transport in rough terrain: the Kirghiz, like the Mongols, are horse people by tradition. There is a saying here that kids learn to ride before they even learn to walk, and looking at the boys from the village I feel it could be true.

Horse guide’s son, Location Boz Uchuk near Karakol

Early in the day the village kids, certainly not older than 10 or 12 years , handled our stallions like they were puppy dogs; if one of them bolted when loading our odd ski-shaped cargo, the kids kept their cool and caught the runaway to try again. Once everything was packed, the locals helped us into the saddles – in retrospect, I’d recommend doing some yoga before attempting to stretch your leg over a pair of skis tied across a horse’s back.

Trek to the yurt camp in Ak Suu

It’s a 3 hour ride up to the yurt camp

It is a cowboy kind of freedom you feel, riding up a snow covered mountain. As we left behind the last bits of civilisation and headed straight into the wilderness, some of us struggled; I had gotten into scrapes before the trip even started. Back in Bishkek there had been fresh snow. Perfect powder conditions are a rare occurrence at the end of March, so we couldn’t help but visit a nearby ski base. There an old, rusty drag lift was my doom: the accident leaving me dangling, head-down, from the cable post like a hog-tied bat. Sitting on a horse just a couple of days later with a broken wrist and bruised, cut torso and thighs, I felt every bone in my body, my wrist pulsing underneath the cast.

Skis tied across the horse’s back

It’s a cowboy kind of feeling trekking up the mountain by horse

By late afternoon we reached our first destination: the yurt camp nestled deep in the valley of Ak Suu at an altitude of 2,400 metres. Some locals had erected the yurts explicitly as a base for backcountry skiing with separate tents for sleeping, eating and an improvised ‘Banja’: a typical Russian sauna for taking a break from the dry cold. Despite the camp, a yurt in the snow is not a common sight in Kyrgyzstan: in the summer months, the locals take nomadic tents out onto the pastures, the ‘jailoos’, inaccessible in the deep snow of winter. In contrast to the warmth of summer camping, the bedroom yurt had tall wooden racks to keep our sleeping bodies far from the frozen ground.

We unloaded the gear and sent the horses back to the valley

Winter yurt camp in Ak Suu – one yurt is for cooking, the other one for sleeping

At dusk, we gathered in the kitchen to eat, drink and tell stories. As well as Norbert and Emilia, I was joined by Vladimir the yurt-keeper, Seroga a mountaineer, and Katia, my Russian-English translator turned friend. I had lived in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital, for 8 months where I met both Katia and Seroga: Katia born in Russia and now running the Southside Guesthouse and organising tours, and Seroga a 28-year-old who has climbed, among other things, the 7,000m Lenin Peak in Kyrgyzstan and Ismoil Somoni Peak in neighbouring Tajikistan. Photos on his phone showed us bodies frozen in avalanches; stark evidence of what could happen when no one has the money to dig you out and bring you home. With his experience on the mountains, Seroga’s biggest challenge of the trip was to lower his pace to match ours. Even heavy, old-school ski adaptors on K2 battered skis and a habit of chain-smoking didn’t give us any advantage.

Warming up with some Chai in the yurt

The evening passed with Vladimir serving dried fish that looked like a shrunken version of Ridley Scott’s Alien whilst Katia translated his stories, telling us about his fishing and hunting and the wildlife of the area. Wolves apparently appear in abundance, whilst the snow leopard – the elusive ‘ghost of the mountain’ – is rare. Brown bears too inhabit the mountains and Vladimir told us how he shot one not far from the camp; Emilia’s eyes growing bigger and bigger as she listened carefully to the story, drinking cup after cup of hot chai. ‘I’m not going out to the toilet tonight!’ she decided at the end, echoing the thoughts of most of the group.

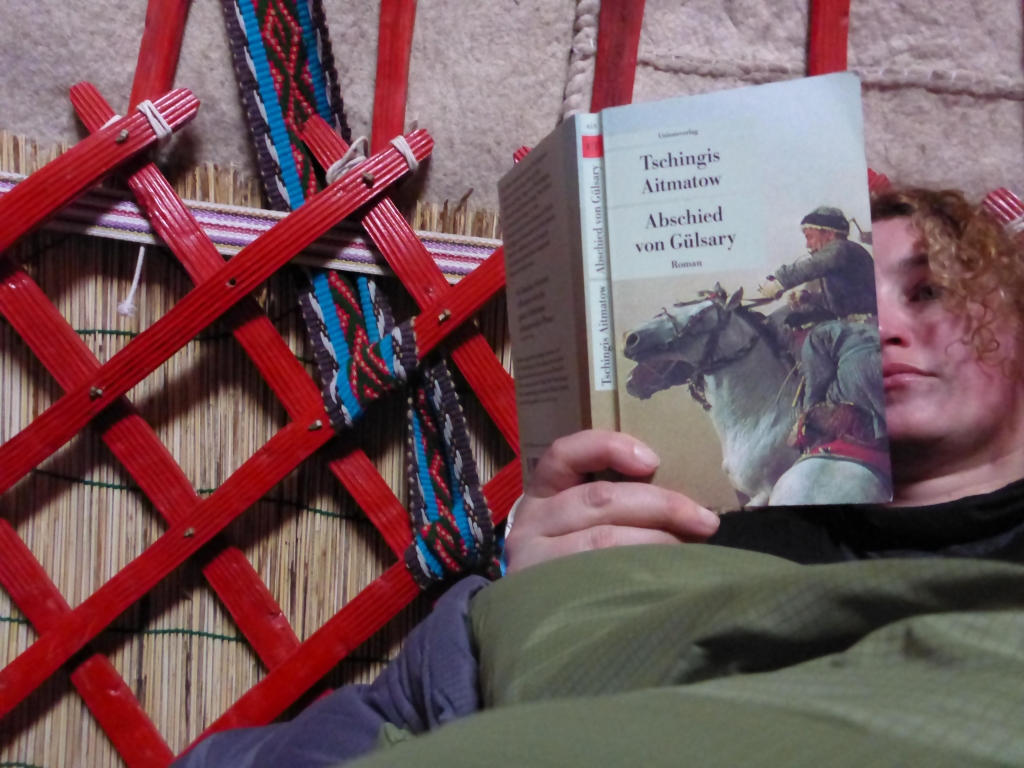

Bedtime stories: The Kyrgyz writer Tschingis Aitmatov is well known all over the wolrd

Sleeping bags on a rack to be far away from the cold ground

The next morning we started early and in darkness we put the skins on our skis, setting off into the seemingly endless valley. When dawn arrived we were rewarded with a magnificent view and took deep lungfuls of crisp mountain air. The valley is remote and made us feel like there wasn’t another soul around for miles, but we were quickly proven wrong as we came across bear tracks in the snow. Seroga explained that there was two sets of tracks, belonging to a mother and her cub, and that they were less than half an hour old. How can you tell? ‘The snow is still warm’ he said, straight-faced.

Ski touring in the valley of Ak Suu: Clean air and a magnificent view

We found bear tracks, just half an hour old

Vladimir’s stories from the night before weighed heavy on our minds and we possessed nothing in our packs to defend ourselves should we come across the cub and its protective mother. Nevertheless, Seroga didn’t seem bothered and walked on. So we did, too.

Kyrgyzstan is a country of contrasts, with dangerous animals living in magnificent landscapes and poverty-stricken mountain villages inhabited by warm and hospitable people. Before we began our trip into the mountains we had stopped for a night in Dzhargalan, a former mining town, where the backyards were full of rusty cars, trash and animal skulls lined with sharp teeth.

Kyrgyzstan full of contrasts e.g. at the Dzhirgalan Freeride Base

Sheep on the road at the Dzhirgalan Freeride Base

Dzhirgalan Freeride Base – a former mining town

skull on the street in Dzhirgalan, probably a dog

Despite their circumstances, the people had invited us joyfully into their homes for a warm cup of chai.

Hot Chai at the guest house in Dzhirgalan

After an evening of planning our next adventure, we arose to a breathtaking panorama of unspoilt landscape, fresh air and a sense of wilderness that radiates from the entire country. A sense inspired by the mentality of a people who have, in their hearts, remained wild and indomitable.

Ski tour from Dzhirgalan

Rest at a small peak near Dzhirgalan

Seroga – our friend and mountain guide

By late morning at 4,470 metres, we found perfect powder conditions on the Kumtor Glacier. The terrain was completely unsuitable for horses, so we changed mount and used snowmobiles: a blast through deep snow and as much fun as skiing through the light, fresh powder.

Snow mobiles at Kumtor glacier – 4400 metres altitude

Getting ready to ski on Kumtor glacier

Breathtaking view from Kumtor glacier

Just a few hours later we felt like we were in a new world: sandy beaches and green fields surrounded the deep blue water of Issyk-Kul, the second biggest mountain lake on Earth.

Setting up the tents at lake Issyk-Kul

Katia – friend and trip organizer

Having descended the mountain to 1,600 metres throughout the day, we set up our tents and bathed in the natural hot springs, easing our muscles in the warm water. Even more refreshing lake Issyk-Kul feels the next morning.

Riding on the shore of lake Issyk-Kul

Refreshing ride in lake Issyk-Kul

Later, we relaxed by a bonfire on the beach, sipping vodka as the sunset bathed the white mountain peaks in a soft reddish light. A horseman drove his herd past our campground and I leaned back, reflecting on the day and on our trip into the mountains of Kyrgyzstan. ‘Could be worse’ I thought to myself, smiling.

Atmosphere at lake Issyk-Kul during sun set

Camp fire at lake Issyk-Kul’s north shore

You can book this kind of trip through Katia’s company Tengry Adventures the Southside Guesthouse in Bishkek.

Taiga, the cat in the sunroom

Katia making breakfast

Chillout area at the Southside Guesthouse

We thank the following people:

Mountain Guide: Sergey Livadnev

Snow Mobile Driver: Viacheslav Sheiko

Trip Organizer: Ekaterina Borisova, Southside Guesthouse, Tengry Adventures

Tour Provider: Emil Ibakov, Alakol Guesthouse, Dzhirgalan Freeride Base

Leave A Comment