“Where the f** is Karakalpakstan?” I wonder when I hear about it the first time. It doesn’t have anything to do with Pakistan, the country. Wikipedia explains: “Karakalpakstan is an autonomous republic at the northwestern end of Uzbekistan. It has an area of 160,000 square kilometres (62,000 sq mi) and a population of about 1.7 Million. The capital is Nukus.” No one can tell me why it is called “autonomous”, because the region is ruled by the government in Tashkent (aka Islom Karimov) just as the rest of Uzbekistan.

October 2013. When my research on Uzbekistan’s first and only animal welfare organization in the capital is complete, I’m on my way to the Aral Sea. I take the 24-hour train to Nukus – of course, not without reservation. In contrast to the Kyrgyz, Uzbeks do not like spontaneous booking.

This time I choose “Platzkart”, the cheapest class (on the Transsiberian I took second class). The nonsubdivided passenger compartment brings up a kind of school camp feeling, cozy and cuddly between all the locals. I am the only tourist and despite my amateurish knowledge of the Russian language, many people are curious and want to talk. With hands, feet and dictionary I am getting to know my seat neighbors. Even the conductor comes over every once in a while and invites me for a cigarette. He is Karakalpak himself and keeps telling me that the people there have a “Sierza khoroshi“, a good heart.

Of course, I cannot get around the usual Central Asian small talk: “Are you married? Do you have children?” When I negate, there are affected eyes and the question: “HOW old are you?” Around here, if you are over 30 and not married, then you are an old maid and a hopeless case. I assure the people that this is normal in Europe. Although they nod and say “I see“, their faces tell me that they are thinking something like “Crazy Europe. They are threatened with extinction!”

In Nukus, I come across the Hotel Jipek Joli (translates to: Silk Road), a stroke of luck, as it turns out. Although, 30 USD for a room per night incl. breakfast are way too expensive for me, there is a yurt in the courtyard of the old hotel building (the new one is around the street corner). I can stay there for 15 USD per night. From time to time the concept of spontaneous travel pays off.

Info: The Uzbeks are not really nomadic people. However, the Karakalpaks have a different cultural background than the rest of the country and actually were nomads in the past, like the Kirghiz and the Kazakhs. Therefore, there are yurts.

Together with an Australian couple, I visit the Savitsky Museum (photo above), a world-renowned art collection that attracts many art lovers in an otherwise unremarkable town. The artist and archaeologist, Igor Savitsky created the collection of paintings and handicrafts of Uzbek and Russian artists in the 1950s. It is said that the museum was “a gem in the desert” and I could not agree more. As for modern art, I have rarely entered a more interesting exhibition. The only catch: The permission for taking photos is outrageously expensive. Therefore, I can show you only a photo of the outside.

As any Central Asian city, Nukus has a bazaar. There you can change dollars in Uzbek S’om (go to the friendly men with the plastic bags), shop for food or find a driver for overland tours.

I didn’t find my driver to the Aral Sea at the bazaar, but by sheer chance. Actually, I had already written off the tour for financial reasons. You need a 4×4 vehicle to get to the water which makes the trip quite expensive. Depending on the tour operator it can cost more than 1,000 USD. OrexCA for example, offers a “Shrinking Aral Sea Tour“ and this is still one of the lower priced agencies. By chance I met another hotel guest who had already booked. He was pleased to share the cost for the transport and in the end there were three of us who did the two–day road trip. Including tent and food, I payed exactly 100 USD.

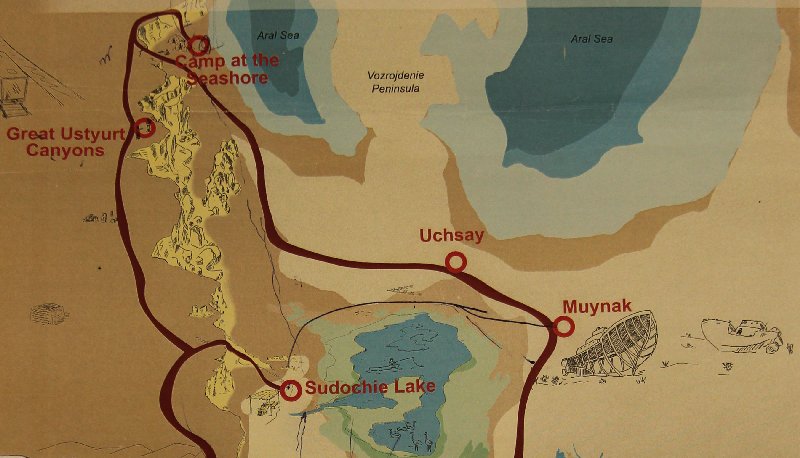

As the map above shows, we drove from Nukus past Sudochie lake to the western shore of the Aral Sea. The next day we continued to the former fishing village Muynak. Here are the details of the tour:

At first glance, Karakalpakstan seems to be just desert, but once you look more closely, you can see old castle ruins and historic buildings (unfortunately also gang-pressed cotton pickers and drilling rigs for natural gas).

First we stop at an old cemetery. The driver turns off the music. “We should respect the dead,” he says. The cemetery looks to me like a shambles: Some graves are fenced, in between are higher buildings and beyond a large area with stacked bricks. To visit the chapel, you have to pay admission. The eagle eye of the cemetery keeper does not miss a single visitor. As soon as he collects the money, he takes us on a tour throughout his realm. Unfortunately, none of us speaks Russian and we can only guess what he is telling us based on his gestures.

After visiting the cemetery, we drive to the ruins of an ancient castle. Actually, it does not look like a ruin, but rather like a rippled and ridged mound. I climb it and get startled, when I suddenly see people in one of the soil grooves. The youngsters speak English and tell me that they had come from Tashkent, just taking a trip. They stayed out here over night and they didn’t have any plans to visit the city. At first glance, it’s four girls, but one of them is tall with very masculine features. I wave my goodbyes and return to the car. On the way I wonder if they are avoiding the city because of the transvestite. Homosexuality is frowned upon in countries of the former Soviet Union and provokes violence.

The trip to the Aral Sea coast takes about 6 hours on bumpy, dusty roads. We are traveling by UAZ, a Russian jeep, which is nearly indestructible because of its simple design. Unfortunately, the constructors also spared the comfort and our butts turn numb soon. As compensation, we are rewarded with quite interesting views: a canyon here, a lake there and an old airplane runway.

After a short walk on the beach, we head back to the cliffs and pitch our tents. Before dinner, I’m going off by myself. The landscape is barren and completely silent. You cannot hear a single sign of life, no crickets chirp, no birds whistle, not even the wind blows. Cliffs and water are glowing in the sunset and somehow this seemingly dead area has its charm. For me the atmosphere feels melancholic, for the sea could be completely gone in just 10 years.

The melancholic mood is quickly gone when a bottle of vodka appears on the picnic blanket. The tour guide who had come with another group of tourists, is fluent in English and translates between us and the drivers. He says in Russian, then in English: “You have to try this vodka, it’s made here in Karakalpakstan.” For fun, I suggest: “Let’s go on Sapoi!” The Russians in Bishkek had taught me the word. It corresponds to “hair of the dog” and means to be constantly drunk for several days. The driver and the guide roll around with laughter. She cannot speak Russian but knows Sapoi. When our guide has recovered, he grins: “I can not believe you know that word. I will invite you tomorrow!”

The next day we cross the salt desert to visit Muynak. The former fishing village used to be located on an island in the south of the lake. There was a fish factory and a port, with about 500 ships calling at Muynak. Now the village is more than 100 kilometers away from the water. Old ships that once anchored off shore are now rusting in the desert sand. They seem to be both, memorial and tourist attraction. There is an information board in Russian and in English and two large drawings of the Aral Sea in 1960 and 2013. Children are playing on the wrecks and colorful graffiti on the outside walls bear witness to many visitors. There is even a fishing museum in the village center, but it is closed on this sunny October morning – the two employees are picking cotton.

Our tour guide keeps his promise. “1001 Nights” is the name of the restaurant he invites me to as soon as we are back in Nukus. I‘m not sure if it is a restaurant or a nightclub. There are fancy waiters with waistcoat and tie, but there is also a 90s dance floor with colorful tiles and a disco ball. A DJ plays Russian charts and the Uzbeks are dragging me onto the dance floor. Desert sand still trickles from my trekking pants and I‘m the only woman in hiking boots – no one seems to bother. As we sit at the table, I get pushed into proposing a toast. Minutes lasting toasts are common around here, but not my style. So I think for a moment, raise my glass and say: “Karakalpakstan has the best vodka in the world!” – Standing ovations.

Travel Tip: If you are traveling alone, especially being a woman, it is certainly not advisable to drink alcohol with strangers. This can backfire.

This time, the only damage was a minging headache. Nevertheless, I‘m still in for a little day trip to the State Nature Reserve Baday–Tugai which is about an hour south of Nukus next to the Amu Darya river. There lives the rare Bukhara deer.

Further information on the trip to the Aral Sea was published in German language in the Swiss travel magazine “Treffpunkt Orient” (Ein Tag am Aralsee) and in English language on Eurasianet.org (Dying Aral Sea Resurected as Tourist Attraction).

Leave A Comment